I don’t often do off script posts since this space belongs

to my writing mind. She is very much on

her own pace despite what is going on around her. 2016 has been a whirlwind! My

family and I have moved out of the Philadelphia area to Louisville, Kentucky.

It was a combination of my departed friend, a mid-life crisis and

some lifestyle choices that favored family. It’s almost the end of a 5 month journey. As

much as I love my 9.5 lb. Sir Kitty Poop-a-lot, we can no longer share a

bathroom.

We are two and a half months into our life in Kentucky. It’s been wonderful. I have found mom’s with whom to run, more time to devote to writing and a network of close friends and family. This past weekend, I was invited to my friend’s church for a workshop called Youth Refugee Adventure. I attended given my own “adventures”.

The program started at 3pm in the Highland Presbyterian Fellowship hall. We were instructed to write our names on a slip of paper. Children and teens

were instructed to write their names on different colored slips of paper. Afterwards, we went to a different station write

down on index one precious item we would take with us if we were forced to flee

our homelands.

The program commenced with a poem written by a ten year old

refugee. The hostess explained that when refugees flee, it is usually preceded

by an act of violence. The poem spoke of bombs in their midst. The child also

questioned when she would feel safe again. The hostess then drew our names and

we were grouped into families of 5 and instructed not to speak. In my mind, I

thought of the qualities that made me and my husband different. I am a writer

that often connects things that don’t really seem to be connected. I am

sometimes impulsive and need to learn things as I experience them. My husband

is careful, calculating and processes situations as they arise. The qualities that make my husband different

from me, I thought, were what might save me in such a situation. At

some point, I assumed hyper vigilance as our names were drawn. We were grouped

into families, ensuring there were children and adults.

We were lead down into a room where we were given a

poster. On this poster we were to write

the identities we assumed as a refugee. My name was Aug Wah. I was the oldest

son from a Burmese family. I had some schooling and my skill was farming. There

were workshop participants all around us given the same instruction. Actually, the only instruction we were given was

“name” and it was given to us by a woman who’s head was wrapped in a scarf and

eyes covered with dark glasses. She was also pointing at us with a blunt object. As we proceeded into the corridors of the church, there was a man with a cigar that instructed us to walk over a string

with bells attached. We were instructed not to let our bodies touch the string.

This was a simulation of the border. Upon reaching the other side, we were told

to go down the elevator where the camp was simulated. One of my “family members” informed me as we

walked down the corridor that our poster was taken by the “guard”.

Prior to this all, our hostess reminded us that as refugees we

were grateful to be in a country with borders. Despite its difficulty, it was

better than the violence in the homelands we departed.

When we arrived at the first checkpoint, it was a problem

that our poster was gone. One of the moms had brought her phone and had taken a

photo of the symbols that represented letters. Being a youth workshop, she

assigned the kids to work on decoding the instructions written in gibberish. It

was a form that asked for our names, ages and country of origin. We were given

a paper that identified us and assigned “primary applicant alien numbers”. There

were blanks next to Health Clinic, Food and Water Distribution, School and

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) Office. We were shuffled

to the first stop, which had a sign for W.H.O., World Health Organization. We

waited with other families for our “health screening”. It was a brief medical

history of our illnesses, our appearance and any recommendations. We were

screened for the lice, obvious health concerns and given a vaccine. The health screening

form and our identification forms had to be signed by the doctor. In real time

the mother and daughter in our group had an emergency and had to leave. I am

normally a person that steps back when a stronger personality emerges. When the mother

and her daughter left, I assumed the senior role.

It was a mistake for us not

to sit and be screened together since one of our group members did not get a

signature on the health screening form. I had to tell the doctor that he was my

brother and offer him my item on the index card, which was a passport. Having

been undocumented, I had never had a valid travel document until the year 2009

and a US passport until 2012. When I wrote “passport” on my index card, I

thought I would obtain food and water on the trail. I also think the documents that have legalized me are among my most valuable possessions.

When we finally did get this signature, we moved on to the

tent labeled “school”. There was a blond blue eyed boy speaking to us in an

unintelligible language. The boy that was supposed to be my younger brother

said he was teaching Mandarin. He would go through the numbers 1 through 10. We

would repeat him and then he would point to a symbol. If we knew it as a family,

we passed. If not we were jailed. The jail was between stations managed by a

woman that wielded a water bottle as if it were gun. Our paper for “school” required

a signature. After it was signed, the teacher shooed us out of his presence.

There were bathrooms were on a balcony on the floor above

us. Every time the doors opened and shut, the way it echoed sounded a little

bit like a boom. It was probably not intentional but gave me the feeling of

being in a bomb shelter.

The path forward was a food distribution tent where they

handed out water in little cups and Cheerios. Our paper was signed as we

were given such items.

The last top was the UNHCR office. We were asked our names, our educations levels and how we might

support ourselves if relocated. We all said farming. The official noted that my

little brother’s identification form was not signed by the WHO physician. We

had to return to the back of the line with the other families waiting.

At some point in our journey, I switched the papers of my

“little brother” so it would appear as if he had collected the correct

documentation. Despite that, it was frustrating to find out we weren’t done. We waited

in line with the other families waiting to get screened. While on line, we

witnessed one of the guards take away a baby. That doll was given to someone

ahead of us in line. Also, one of the boys/actors with a physician’s mask was

requesting a donut from the food distribution center.

One of the words that was intelligible to us was “security!” The food

worker screamed at the boy who tried to get a donut and the guards appeared to search for him in our ranks.

When we arrived at the front of the line with the “doctor”

who had seen us, he signed the paper. It looked like he was searching for

something more. I offered him my index card with “passport” written on it. He

didn’t seem that interested. Other participants had written money, food, water,

jewelry, photos and cell phones. This seemed to be items of interest for the

guards or doctors in such scenarios. Such items were pocketed by the camp facilitators. My friend commented if that were indeed a prized possession by a refugee, they were gone.

We waited until the woman that had seen us first was

available again. She checked over our documents once more. Finally, she said

that given our level of education that she felt we did not have enough to leave

the camp. She wrote denied on our paperwork.

At that point we were escorted up the stairs and asked to

fill out a questionnaire or journal. Questions included:

·

What is pushing you to leave your country?

·

What are you hoping to find on the other side of

the border?

·

What are you afraid of finding across the

border?

·

What was it like trying to communicate to border

guards and camp officials?

·

How did you feel about the process?

·

What was the most frustrating part of your

refugee experience?

·

What would you do if you lived in a camp for

several years?

·

How does this experience change the way you

understand “refugees?”

·

What similarities do you share with “refugees”?

·

What import qualities do refugees bring to our

communities?

As we made our way back to the fellowship hall, we were

debriefed by the facilitators. In order to stay true to the refugee statistic of

1% acceptance, only one of the families was approved entry into a free country.

At this point I asked what the refugees did that were not approved to leave the

camp. I was told the tenure at the camp

was undefined, that some were born and died there.

We were shown a video from United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or UN Refugee Agency. We were also shown a

photo of the Yum center at its fullest during a University of Louisville

basketball game, which holds about 20,000 people.

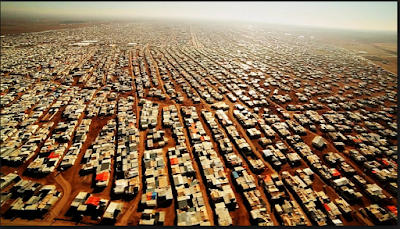

From regions like Syria, Africa, Asia there were 16.1 million refugees. We were also shown different borders and refugee camps in these areas. Our facilitator felt that these were the kinds of photos that could be shown at our venue.

From regions like Syria, Africa, Asia there were 16.1 million refugees. We were also shown different borders and refugee camps in these areas. Our facilitator felt that these were the kinds of photos that could be shown at our venue.

|

| Some images courtesy of Google |

After the debriefing, we were invited to have dinner. We

were served rice (with tomato, vegetables or sausage), sweet potatoes, fruit,

humus and vegetables. The runner in me thought it was a clean meal. Others

commented its modesty seemed intentional given the workshop. We said grace

prior to our meal and then we were introduced to Sevraine, a refugee from

Burundi. The Pastor told Sevraine that we were lucky to be a part of the

journey. Sevraine told us the story of his family. He fled his country because

he did not want to be involved with the political party that sought his

alliance. Defiance meant death. He was a chemistry teacher that became a member of parliament. Upon

leaving, he had to go through the process of bringing his family here. When he

was reunited with his daughters, the youngest of them had no memory of him.

Despite his family’s forced migration, he did not wear the scars of violence in

his demeanor. He told us he was starting to teach in the public school system

and he was grateful to be supported by the community. The dinner was concluded by two of Sevraine’s

daughters performing a traditional dance. It was hard to imagine

those vibrant beautiful girls not in the setting of a free country that I have

come to take for granted.

It is hard to admit how much of it all I have taken for

granted railing against an imperfect system. Yes I have been undocumented and

yes we “lose time” aging out of processes. As I have aged out of such

benefits, I had experiences; I started a family, earned 2 degrees and was lucky enough to be able to adjust my status. I have no

concept of “losing time” at a refugee camp. I have no concept of not having food,

shelter, healthcare and my family. Privilege has many shades. I have lived in

its shadows, imperfections and even in this workshop, privilege showed me

the world beyond my own.

I honestly don’t even know how to conclude this essay. I

write about my undocumented brothers and sisters who fight for systematic

change to legalize. There are specific things our government can do to affect change with the 11 million without legal status.

In the case of refugees, there are so many governing bodies

that need to come together to affect change. The size of this crisis is incomprehensible to me in bodies, borders and the vastness of such lands that contain refugee camps. What I hope for now is the ability to comprehend a solution and if the opportunity presents itself, be a part of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.